Bavaria’s bishops criticize AfD after election success

Bishops in the southern German state sharply criticized the Alternative for Germany after the party made gains in state elections.

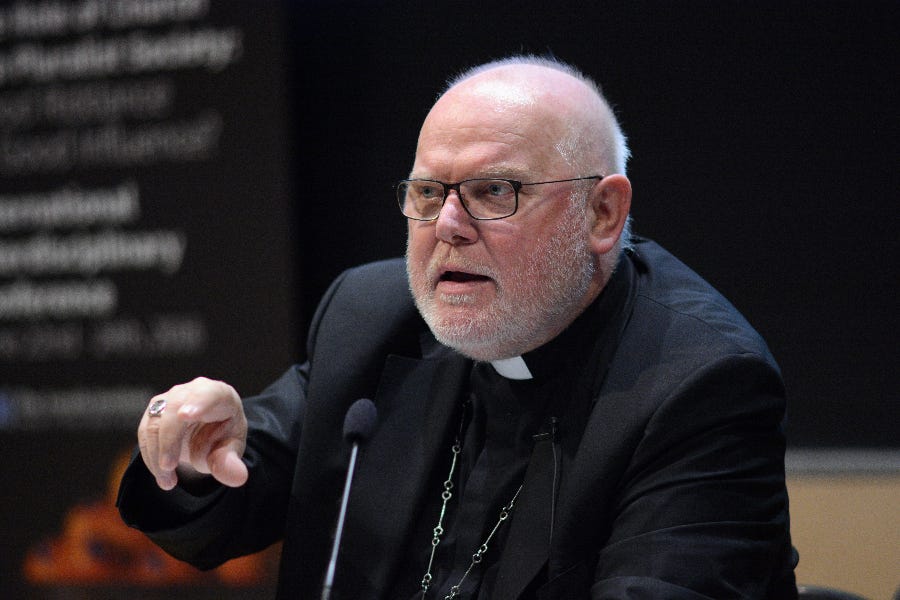

The bishops in the southern German state of Bavaria sharply criticized the Alternative for Germany (AfD) political party Thursday after it made gains in state elections.

Members of the Freising Bishops’ Conference said Nov. 30 that they were “shocked by the rise of political forces that…