As Israel and the world marks the one-year anniversary of the October 7 massacres, heads of state continue to call for peace, and for restraint by Tel Aviv in response to the recent rocket attacks by Iran.

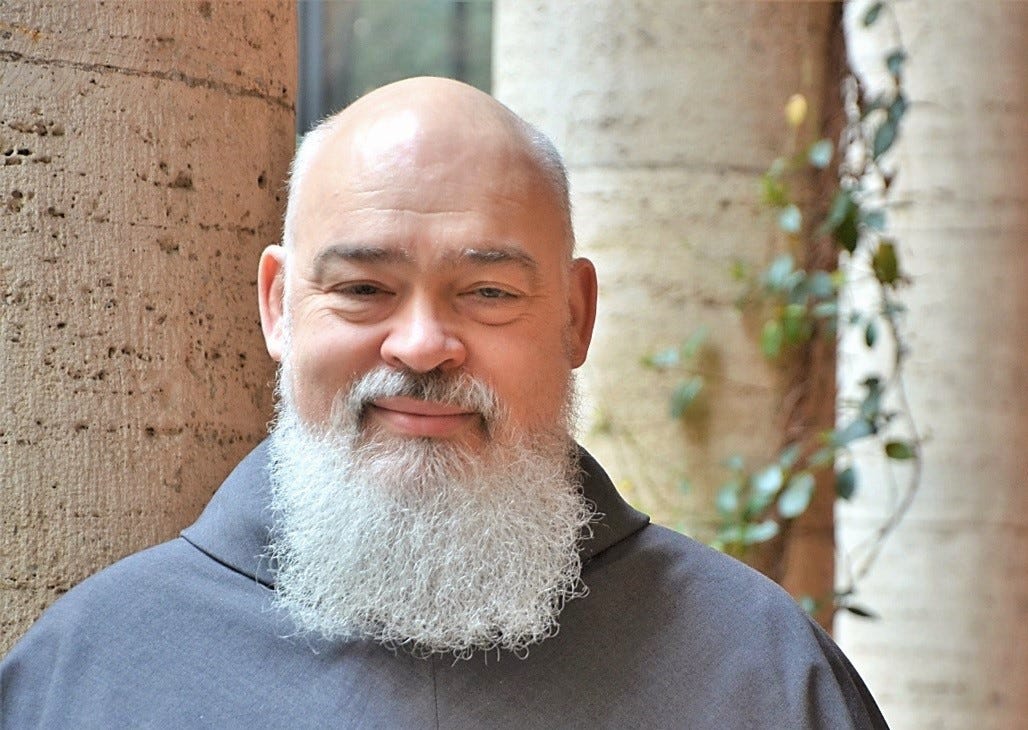

While expressing sadness and closeness to victims of the violence on the anniversary of the attacks, in the last week Pope Francis’ personal peace envoy issued a striking assessment of Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, and on Sunday the pope named the Archbishop of Tehran, Dominique Joseph Mathieu OFM Conv., as a cardinal.

Both interventions are striking, in as much as they seem to signal a more direct willingness to engage in the geopolitics of an ongoing conflict in the Middle East then Pope Francis and his Vatican have shown for other regions.

But is the Vatican singling the Middle East out for special criticism, or is the Holy See trying to create itself a seat at the table to work for peace?

—

During a question and answer session on October 2, following the presentation of his new book, “The God of the Fathers: The great novel of the Bible,” Cardinal Matteo Zuppi was asked what, as the pope’s personal global peace envoy, he would like to say to Netanyahu.

“That he does not do the good of his people,” the cardinal answered simply, “not of the others, it’s obvious.”

While criticism of Netanyahu’s government, and the means by which it has prosecuted the conflict in Gaza and now Lebanon is not hard to find, including from the Vatican, flatly accusing a head of government of failing to work for his own country's good is unusually stark and personal — some might say undiplomatic — coming from someone holding a senior international diplomatic brief.

Zuppi has form in this regard, having previously called Hamas “the worst enemy of the Palestinian people,” but it seems to be only on the Middle East that he is so outspoken.

Since being designated as the pope’s personal envoy in 2023, Zuppi has been involved in talks with governments about conflicts across the globe, meeting with officials from and in Washington, Kyiv, Moscow, and Beijing in a bid to press the case for peace.

In doing so, Zuppi has often been very measured in his approach — celebrating, for example, his “cordial” conversations with the Chinese government, despite its domestic genocide of the Uighur people and the “disappeared” status of several Catholic clergy in the country.

As questions last week turned from Israel to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the cardinal became immediately more circumspect. “We must bring peace and justice together, justice must meet peace and vice versa,” he said.

Following Zuppi’s appointment as freelance papal representative, Vatican diplomacy has come under considerable scrutiny for appearing at times to be over-diplomatic and complicated to the point of confusion when dealing with issues like China or the war in Ukraine.

But the conflict in the Middle East has emerged as a notable exception to Vatican diplomatic reserve.

Following the Hamas atrocities one year ago, the Holy See was unequivocal in its condemnation, with Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Parolin referencing at the time “the war that has been provoked” by the killing of so many “wholly innocent” civilians.

But if the casus belli was clear last October, by February Parolin was equally clear on Israel prosecuting that war but what Rome appears to consider illegitimate means. “The right to defense of Israel must be proportionate,” the cardinal said, “and certainly with 30,000 deaths [Israel’s response] is not."

On the other hand, as the war in Ukraine has continued to escalate after the Ukrainian offensive into Russian territory, the Holy See has been less directly critical of the leadership and tactics of either side, instead concentrating its efforts and attention on Cardinal Zuppi’s attempts to negotiate the return of kidnapped Ukrainians, including children, trafficked from occupied territories into Russia.

That sensitivity has led to several instances in which Ukrainians, including Ukrainian Catholics, have voiced criticism of the Vatican failing to take a hard enough line when speaking about Russia.

It is also widely seen as the reason the pope has resisted, until last weekend, appointing a cardinal from the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church — despite it being the largest Eastern Church in communion with Rome. Many predicted, and many others advocated, that Francis should elevate Major Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk, both before the Russian invasion and after.

Apart from recognizing the place of the Ukrainian Church in the Catholic communion, installing a cardinal in Kyiv has been argued by many as a potentially dramatic gesture of papal solidarity with the Ukrainian Church and people.

Instead Francis chose on Sunday to announce he would elevate the head of the Ukrainian Eparchy of Melbourne, Australia, in a move which, on paper, supplies two notable gaps in a future conclave without either choosing between the major local Latin bishops in Australia or thumbing the delicate geopolitical-ecclesiastical scales between Ukraine and Russia.

Yet Francis appeared to show no such delicacy in the appointment of the Archbishop of Tehran-Isfahan to the college of cardinals.

Archbishop Mathieu has not, in his three years in the post, shown himself to be a maker of international headlines and, absent the current conflict, Tehran would have qualified easily as a “peripheral” posting in the global Church. But by announcing his elevation to the college so soon after the Iranian rocket attack on Israel, and on the eve of the Oct. 7 anniversary, it is difficult not to read a wider and more immediate significance to the appointment.

As the world waits for an eventual retaliation from Tel Aviv against Iran, Francis issued a letter to the Catholics of the Middle East on the October 7 anniversary, lamenting “the shameful inability of the international community and the most powerful countries to silence the weapons and put an end to the tragedy of war.”

“Anger is growing, along with the desire for revenge, while it seems that few people care about what is most needed and what is most desired: dialogue and peace,” the pope said. And it is possible that the pope’s decision to install a cardinal in Tehran could be a calculated effort to force a more direct role for the Vatican in peace negotiations, as a compliment to Cardinal Pierrebattista Pizzaballa in Jerusalem.

A superficial reading of Mathieu’s elevation is as a kind of overt mark of papal sympathy for Iran against Israel, of the kind many hoped for in calling for Shevchuk’s elevation prior to and following the Russian invasion.

A more subtle and sui genres reading of the scene might hold that Francis is elevating a voice inside Iran to call for peace and restraint, much as Pizzaballa has done in Israel, giving Mathieu an international status and — hopefully — the diplomatic cover to become a more public voice in what is one of the most politically and socially repressive countries in the world.

If the new cardinal proves able (and willing) to do so, Zuppi’s personal criticism of Netanyahu and the Vatican’s pointed calls for “proportionality” by Israel could end up serving as diplomatic credibility in the bank for Mathieu to draw on.

Of course, if Mathieu does not emerge either as a new voice for peace or diplomatic player in the escalating regional conflict, many will view his appointment as, at best, an opportunity wasted.