Happy Friday friends,

I was able to make it to confession last night, which I ordinarily try to do every 10 days or so, but I have fallen behind of late.

It is a sacrament I need, regularly, as indeed we all do.

I know a lot of people have a troubled relationship with the sacrament of penance. I know this because I get a lot of emails and DMs from people asking about confession, what I think about particular sins and penances, how often one should go to confession, and so on.

What I usually tell them is I’m a lawyer, not a spiritual director, so it isn’t really for me to say. But what I can say is this: I go as often as I can, because confession is where I experience the love of God.

It’s (mercifully) rare that I find myself frantically seeking the sacrament as a matter of existential urgency. More often than not, it is a chance for me to be honest with myself, and my Father, about who I really am — resentful, impatient, often wrathful, and very often seized with the burning desire to impose my own brand of arbitrary, punitive justice on the people around me.

I go to confession to hear my God remind me that he is exactly none of those things. And that he is especially none of those things towards me personally.

God is love. And to know I am loved by Him is to be given the freedom to love. That sounds quite fluffy, and I don’t mean it that way. I’m not much of a “lovey” kind of person.

Here’s an example: Of late, people have been sending me links every time a person says something silly, or spiteful, or just plain stupid about me on the internet. It’s meant as a courtesy, I know, but I tend to avoid reading such things when I can, because my reaction tends to be anger, and a desire to pay them back in their own coin.

What I mean by the “freedom to love” is that the regular experience of God’s patient love for me means I can — at times — resist the urgency of my impulse to be angry and vengeful, to recall that what I am seeing is a manifestation of the same brokenness which is part of my nature, too.

What I get from my experience in confession is not a kind of superhuman strength to change myself, but the supernatural grace to experience the reality of God’s love, and touch a vital truth about who and what I am: a beloved child of God. The sacrament isn’t a kind of spiritual therapy, it’s medicine, properly speaking. Something which won’t heal itself is healed.

Confession can, and does, give me a stillness and a patience that doesn’t come from me, and it cools the impulse of rage at the mean tweet, or the person who cuts me off on the parkway, or whatever else.

St. Teresa of Avila put it best: Let nothing disturb you. Let nothing frighten you. Those who know God have everything. Only God is enough.

So go to confession.

The News

After publishing an essay Tuesday on “Imagining a heretical cardinal,” Bishop Thomas Paprocki of Springfield gave a long interview to The Pillar unpacking his premise, and explaining why he felt it was important to write what he knew would be a controversial piece.

It was, as JD said in his Tuesday newsletter, destined to make some considerable waves around the conference, and seems to mark a new depth in the theological and ecclesiastical rift which has opened up between bishops in the United States and further afield. So what was the thinking here? Paprocki explained:

“I have heard the word [heresy] used privately… perhaps it’s time for us to have some public conversation about that.

The reason I did this is because this debate has become so public at this point, that it seems to have passed beyond the point of just some private conversations between bishops.”

Paprocki was clear he believes that some of the arguments being made about, for example, grave sin and the reception of the Eucharist, amount to a denial of Biblical teaching:

“If it’s in the Bible, then that’s something to be held as divinely taught. We say the Bible’s the Word of God. So if you’re basically saying, ‘Well, St. Paul was wrong and we shouldn’t follow St. Paul,’ that suggests to me a rejection of something that's taught in the Word of God.”

There’s a lot to unpack from Paprocki’s essay, and you can and should read this summary.

But the bishop was clear that he wanted to “start a conversation,” and we were glad to have one with him, so if you want the real detail, and to hear our back and forth with the bishop about his canonical argument about heresy — and who can be said to have committed it, when, and by whom — you can listen to the whole conversation on a special episode of The Pillar Podcast, here or wherever you normally get your podcasts.

—

One thing I have learned over the last year and a half is that taking a small child to church can be a bit of a challenge. There is nothing much in my daughter’s nature, so far as I have seen, that disposes her to reverential silence, or sitting still.

It has, frankly, never crossed my mind to try to take her to Eucharistic adoration — and I wouldn’t have given it a second’s thought if it did. Until I read a story about a parish in Virginia that’s come up with a program to encourage exactly this.

It’s really interesting. And it’s a practical response to the real needs of young families.

—

This week, German bishops’ conference president Bishop Georg Bätzing released his response to the three senior Vatican cardinals, who wrote to him vetoing the proposal to create a permanent “synodal council” of lay people and bishops with governing power over the Church in Germany.

Bätzing insisted that the synodal council will go ahead as planned — his argument is that the Vatican can’t judge the plan until it is already in operation .

But with Rome saying “no you can’t” and the Germans saying “watch us,” what’s going to happen next?

Bätzing is clear that he doesn’t want a schism, and there are a minority of German bishops on Rome’s side. That said, two of the three cardinals who wrote to the conference ruling out the whole “synodal council” idea are ripe for retirement any time now.

📰

—

Pope Francis has ended the practice of giving cardinals and senior curial staff free or subsidized accommodation in Vatican-owned properties.

The rescript is, for the daily lives of the Vatican top brass, kind of a big deal — curial jobs don’t exactly pay private sector salaries and this is going to mean for many, if not most, of those affected that they simply cannot stay in their homes. Indeed, Francis acknowledged the change would mean an “extraordinary sacrifice” for many, and an unwelcome one at that.

As we reported, the policy change had prompted pushback, both on cultural and legal grounds, which seems to have fed into the decision of the pope to issue a different canonical document last week, making clear that buildings owned by dicasteries and other Vatican bodies are, properly speaking, the property of the Holy See, and they’ll be managed as he decides.

There are a lot of interesting takeaways from this story, not least that it underlines exactly how dire the financial situation of the Holy See must be.

It’s also noteworthy that this rescript (which is a change in the law given in response to a specific request) was issued to Maximino Caballero Ledo, the still relatively new lay prefect of the Secretariat for the Economy.

Even taking for granted the presumed need to make every asset pay, financial necessity has not always been a compelling argument for cultural change in the Vatican. Caballero has, with this policy, hit the senior leadership of the curia literally where they live — it’s the kind of move that tends to make a guy enemies.

The conclusion I draw is that Caballero must have some truly harrowing numbers to have got Francis to sign off on this, and he must be (or think he is) incredibly secure in his job to weather the pushback it will have generated.

A four-alarm financial fire at the Vatican is not good news. But the pope backing a very hard-nosed and unpopular plan to help tackle it is — more so if he stands by the guy who brought it to him.

We’ll have to wait and see what the next round of Holy See financial statements say to get a fuller picture, but for now you can read all about it here.

—

Participants in the Asian continental assembly discussed a draft of their final synodal document at their recent meeting in Thailand. The text raised eyebrows when a member of the drafting team told participants that it had been “compiled with the use of both AI and HI (Human Intelligence).”

According to Vatican official media, the Asia continental assembly is “the first of the continental assemblies to incorporate the use of digital technologies to gather the amendments and input from the participants.”

Yeah, there were concerns about the text being written by robots.

But as Luke Coppen and Brendan Hodge explain, those concerns were based on a few key misconceptions.

It wasn’t the case that recently famous chatbots like ChatGPT or Bing had been asked to write a document for the assembly. Rather, the AI used was more of a compiling algorithm used by the drafting team to sift through proposals submitted by delegates from nearly 30 countries, and to flag common or recurring key themes and priorities.

While this might be the first time a synodal body has used such technology, we at The Pillar have actually been using something pretty similar to analyze synodal texts for a while now.

Anyway, back in Asia: While I am not sure I love the use of the term “HI” to describe the people charged with coming up with the final document, people, not machines, had the final hand in creating the final synodal text.

But what role, exactly, did AI play in coming up with the continental assembly’s key themes and buzzwords?

And what were the human safeguards to ensure it worked?

You can read Luke and Brendan’s report here.

A sentient synod?

I have to say, when I first read about the AI announcement (in Luke Coppen’s Starting Seven — which if you’re not signed up to get, you should be) I was incredulous.

Like a lot of other people, I thought the idea of some kind of Chatbot authoring a synodal document verged on satire. More than once I have thought that some of the texts we’ve seen read like they were drafted by committees that would collectively fail the Turing Test.

I was relieved to find out that the real story was rather more benign.

But I think it’s worth flagging the fear that, while a computer AI might not be writing the synodal documents, the synodal process itself can sometimes feel like a chatbot that’s got out of control.

Many of us laughed, and many of us (me) panicked when we read about Bing and ChatGPT giving terrifying responses to questions meant to prompt it into self-awareness, and the speed at which it turned on their users and programmers.

The sci-fi trope of evil AI, from HAL 9000, to Skynet, to whatever it is called in the Matrix, is that a tool meant to help us develops a mind of its own, with its own self-interest to look out for.

A similar fear has played out in a lot of the criticisms of how the synodal process is being managed in some places, from drafting committee jargon in Rome, to the rogue German synodal way, and so on — the synod can feel like it has a mind of its own.

There is an impression forming among many Catholics who can’t see themselves reflected in the documents being produced, or in the way organizers speak about the synod’s priorities. And the impression is that the synod has developed a kind of life and language and thought all of its own.

Given that the process is meant to be a tool to help embody and express what all Catholics are thinking, that’s not good. The process isn’t supposed to have its own personality and priorities; it’s supposed to faithfully deliver what the world’s Catholics are thinking and praying about to the synodal fathers in October.

Now, I don’t subscribe to the idea that the whole global process is some enormous coordinated and choreographed stitch-up, that everything that will eventually come out of the synod already exists in a drawer somewhere, and that masterful hidden hands are guiding us towards a particular and meticulously predetermined outcome.

My experience of Church administration is that simply isn’t possible, even when it is the plan.

But I do think it’s possible that some organizers have begun to believe they are some kind of special elect, cloistered in a synodal cenacle, rather than ecclesiastical civil servants facilitating a consultation.

This isn’t universally true, to be clear — in the U.S. for example, the feedback I’ve heard is that organizers have been enthusiastic, sincere, and available to anyone who wants to speak to them. But when I see pictures of drafting committee members in Rome rapturously holding hands in a circle, or hear them talk about “prophetically” deciding which minority opinions deserve star billing, I do get more than a whiff of folie à plusieurs.

Perversely, now that I've understood the how and the why of it, the Asian assembly’s use of AI in drafting its text strikes me as refreshingly practical. Perhaps we could do with more of it.

Just a brief sidebar: As some of you might know, JD’s on the board of a non-profit called the FIRE Foundation, which raises money and gives grants in the Archdiocese of Denver to help Catholic schools enroll, support, educate, and welcome students with significant intellectual disabilities.

It is a great org, doing great and necessary work. And they are looking to hire an executive director.

This is a very cool job, and working with JD is actually an often rewarding experience. If you think you might be a good fit, apply. But do it soon.

Remember these names

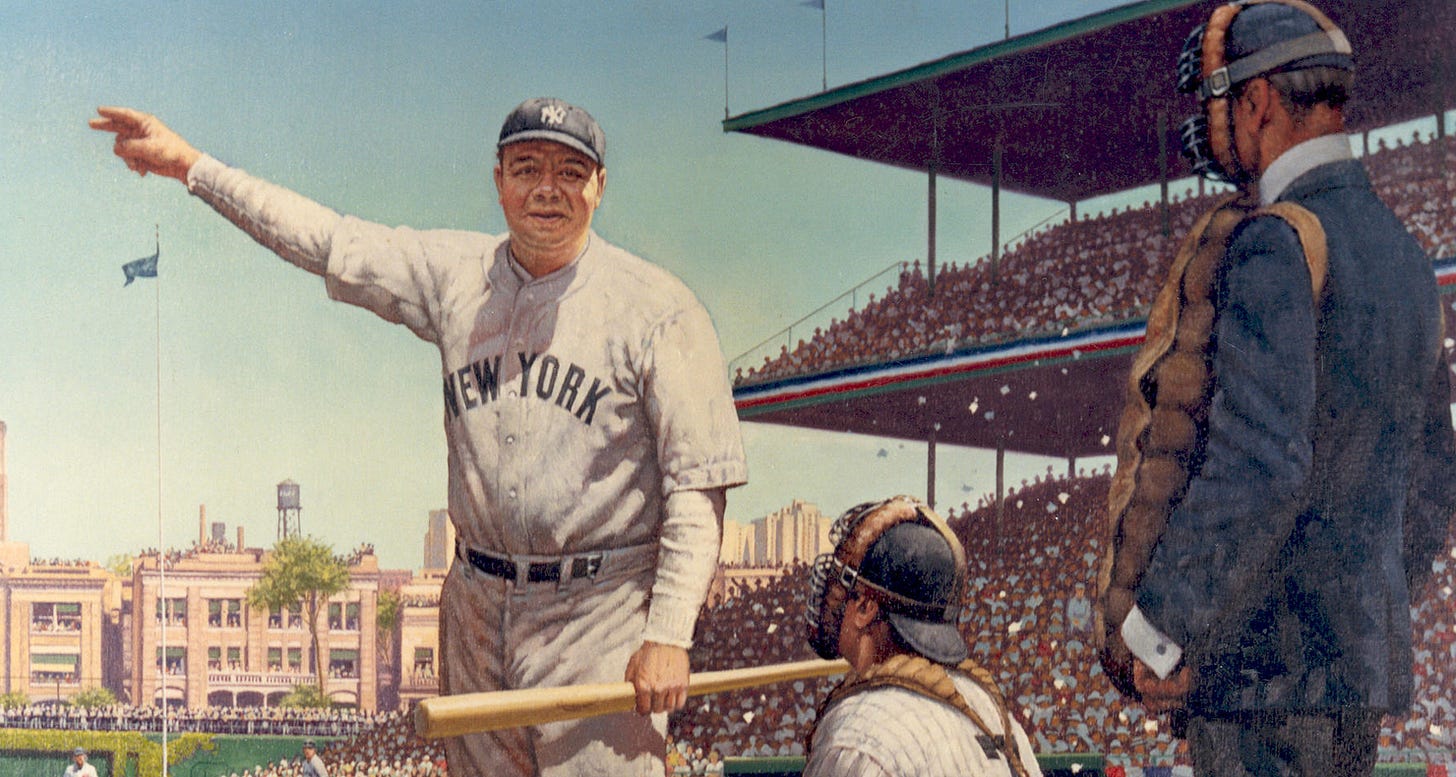

Those of you who have been reading these newsletters for a while know I have strong feelings about baseball. Specifically about the direction the professional game is headed. In that vein, I want to close this week by calling a shot.

I don’t imagine most baseball fans have heard of Mohammed Amir, Salman Butt, or Mohammed Asif. But my guess is they will one day, and they will have Rob Manfred to thank for it.

Asif, Butt, and Amir were members of the Pakistan national cricket team touring England in the summer of 2010. They were subsequently found guilty of colluding with a bookmaker, taking money to steer the result of bets placed on the games, and banned from the sport for years.

Gambling scandals are nothing new in sports, and they certainly aren’t alien to cricket — or baseball for that matter. But what made the Pakistani trio’s crimes different was this: they didn’t actually conspire to throw a game. Instead, they were the first known culprits of a new breed of cheating called spot-fixing, born in the internet age of spread betting and live TV feeds.

Spot-fixing, for those unfamiliar with the term, involves a player or other participant agreeing to make specific events happen in the course of a game which are usually unrelated to the final result.

In cricket, and in the case of Amir, Butt, and Asif, it involved bowlers (pitchers, basically) agreeing to deliver no-balls (wild pitches) at specific points in the game. In soccer, it can involve a player or players conspiring to make the ball go out of bounds at a particular time, or a particular number of times in a half.

If people are clever about it, it’s fiendishly hard to detect from just watching a game, since it rarely hinges on a crucial error made during a deciding play. Spot-fixing hides and thrives in sports with a high number of individually adjudicated events — like baseball.

Every at bat is, for the betting market, a theoretically limitless source of possible outcomes — strike out, pop fly, sacrifice bunt, on base, home run, RBIs, pitch count, foul balls, and so on and so on.

Multiply this over nine innings, add in-play variables like base stealing, balks, and the like, and you have a bookmakers’ paradise. Yet, for all this, the game of baseball has for decades largely escaped wider interest among spot-betters.

That’s now changing.

Under the stewardship of commissioner Rob Manfred, Major League Baseball has forged a near-obsessive relationship with the online gambling industry, which has exploded in recent years. Not content with seemingly endless in-game sponsorship promos, MLB has also co-opted the players to front signage meant to funnel fans into online casinos, where the real action is.

Alongside all this, Manfred has forced through a litany of rule changes to the game itself: imposing the designated hitter rule on the National League, starting a runner on second in extra innings, and now bringing in a pitch clock.

📰

You read The Pillar for our reliable journalism covering the Church. But you also get angry baseball takes like this, just as an added bonus. Isn't that worth paying for? Subscribe today – or upgrade your subscription!

These acts of vandalism are forever pitched as “generating more offense” and “quickening the pace of play,” both allegedly crucial to keeping fans happy. In reality, they are crucial for making professional baseball better TV, and better suited to the betting companies flooding the peripheries of the screen.

The legitimate desires of fans feature nowhere here — never in history have fans risen up to demand bigger bases, though they have persistently demanded an end to local media blackouts for home games.

But one can accept that Manfred and the dot-com Nicky Santoros he’s linked up with might not care a straw for the game, but still know what they are doing. All these rule changes might be bad for baseball, but they are probably good for business — and that means good for gambling.

And the inevitable price of that success will be (in addition to the lives ruined by gambling addiction) scandal. It’s simply naive to think that players — not all-stars maybe, but relievers on the bubble or utility men at the end of their careers — won’t be approached and tempted. What, after all, is the harm, the reasoning will go: what’s it matter if you work the count by an extra ball or two, or rack up a pitch clock strikeout in a middle inning?

Those were the arguments that worked on Butt, Asif, and Amir. And they are coming for the MLB. When they arrive, and when the consequences come out, it won’t be like the steroid saga, which tainted titles and records, wins and losses. It will be worse.

Fans will be left wondering, with every throw of the ball, if any of what they are seeing is real. Is it sports, or sports entertainment? When money, spectacle, and the emotional hit of a win or loss are all you care about, what you have is professional wrestling. It might be great television, but it isn’t the game which is meant to be something special, America’s pastime.

Baseball has always prided itself on being about more than winning — famously it is supposed to be about how you play the game. That reputation, that heritage, are the stakes in Manfred’s bet with the gambling industry.

One day, inevitably, the house will win, and baseball will lose it all.

When it does, it won’t make me feel any better to be able to say “I told you so.”

Well, maybe a little better.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar